Sharing ideas and inspiration for engagement, inclusion, and excellence in STEM

Note: A version of this story was originally posted on the Vernier website in July 2021.

Dr. Jerry Easdon is a proponent of using inquiry-based, hands-on experiments to reinforce key concepts in his General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry courses at the College of the Ozarks in Point Lookout, Missouri.

So, when he was unable to find appropriate and engaging experiments to teach students about metabolism and fermentation, he created his own. The result? Two innovative—and potentially once-in-a-lifetime—learning experiences.

Fermentation on the Farm

The College of the Ozarks is a work-study institution located on a large farm. It is also home to a dairy that is about two blocks from the chemistry classrooms.

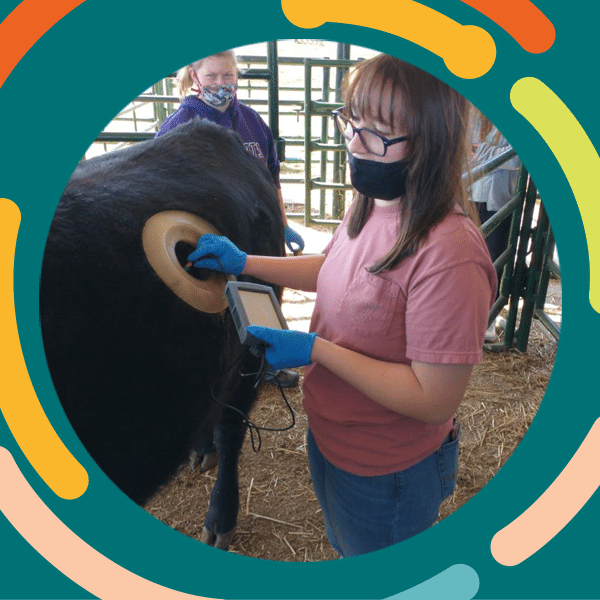

Easdon saw the opportunity to integrate what students were learning in class with the rich agricultural resources and livestock available on campus, including a fistulated cow named Tallulah, who was rescued from slaughter and has become a sort of cherished pet to everyone on campus.

After coordinating with the college’s agriculture department, students visited the dairy. There, they observed the fermentation and metabolism processes taking place inside the cow and collected live data using Vernier CO2 gas sensors, pH sensors, and temperature probes.

“If they wanted to participate, students could actually reach into the cavity of the cow and use the sensors to measure different values of the cow’s rumen fluid,” Easdon said. “They could even see the feed being processed inside the cow’s stomach chamber.”

Further, a faculty member in the college’s agriculture department provided the students with additional information.

“This really complemented what we were learning in class and provided students with such a neat opportunity to really see—and measure—fermentation and metabolism processes in action,” Easdon said. “I think it’s something they’ll definitely remember.”

Getting Creative with Kombucha

In addition to hands-on data collection with Tallulah the cow, Easdon provided students with the opportunity to prepare kombucha and follow the production of the drink’s metabolites over time. This involved setting up a large-scale fermenter with O2 gas sensors, CO2 gas sensors, pH sensors, and ethanol sensors.

“Under low-oxygen situations, fermentation can occur in a variety of foods and drinks,” Easdon said. “With this experiment, students worked in small groups to create their own variation of kombucha and measure different aspects of the fermentation process using Vernier sensors. This helped them experiment with different variables—such as using hard water versus soft water—and really understand what the fermentation process looks like.”

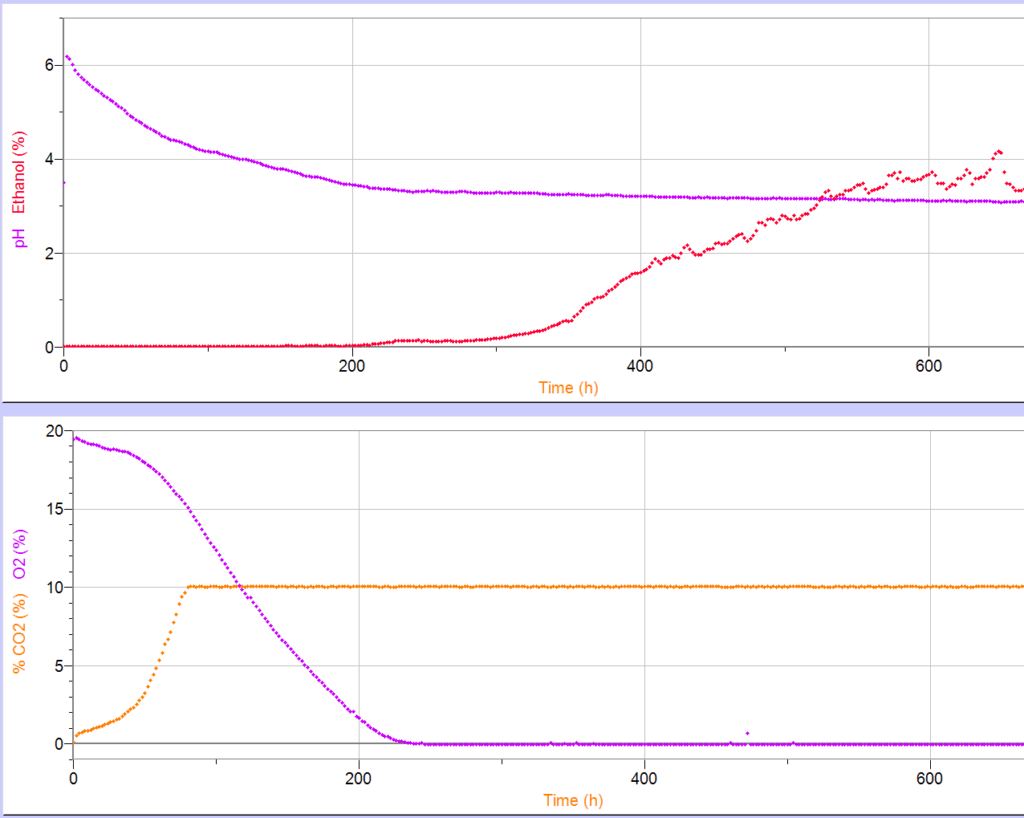

Throughout the fermentation process, students were able to collect and analyze pH and ethanol data, as well as graph acetic acid and ethanol production, using Logger Pro® software.

“Students saw normal oxidative metabolism as O2 levels decreased and CO2 increased,” Easdon said. “As the oxygen level approached zero percent, ethanol started to show up and increase in concentration.”

The Importance of Hands-On Experimentation

According to Easdon, hands-on science learning opportunities “reinforce what’s being taught in lecture and provide a great way to engage students in scientific discovery.”

“Students are always drawn to activities that let them solve problems and make real-world connections in interesting ways,” he added.

“And students are so creative and like to explore. Oftentimes, if you just provide the technology, students can come up with really good experiments by themselves and take ownership of their learning.”

Easdon also encourages other college educators to seek out ideas and collaboration opportunities with different departments at their own institutions.

“I have had many great suggestions for projects from my colleagues in art, family and consumer science, physical education, engineering, and psychology,” he said.

Although he has retired, Easdon continues to follow up on experiments he developed to support and inspire chemistry students at the College of the Ozarks.

“We have a good amount of data-collection technology available for students to access, so I want to continue to come up with ways for them—and myself—to innovate,” he said.

Download Dr. Jerry Easdon’s Experiment Materials and Sample Data*

* These files were created exclusively by Easdon and are shared here as a courtesy for reference purposes only.

Focused on organic chemistry and biochemistry, Dr. Jerry Easdon taught at the College of the Ozarks for more than 30 years.

Share this Article

Sign up for our newsletter

Stay in the loop! Beyond Measure delivers monthly updates on the latest news, ideas, and STEM resources from Vernier.